LESSON 4

How Do Scientists Explore the Deep?

Introduction:

How Do Scientists Explore the Deep?

The deep ocean is the most unexplored region on Earth—dark, vast, and often unreachable. So how do scientists learn about it? With the help of cutting-edge technology, determination, and a thirst for discovery.

1. The Challenges of Exploring the Deep

Exploring the deep ocean isn’t easy. Scientists must overcome:

Did you know?

Most of the ocean remains a mystery—over 80% of it is still unmapped and unexplored.

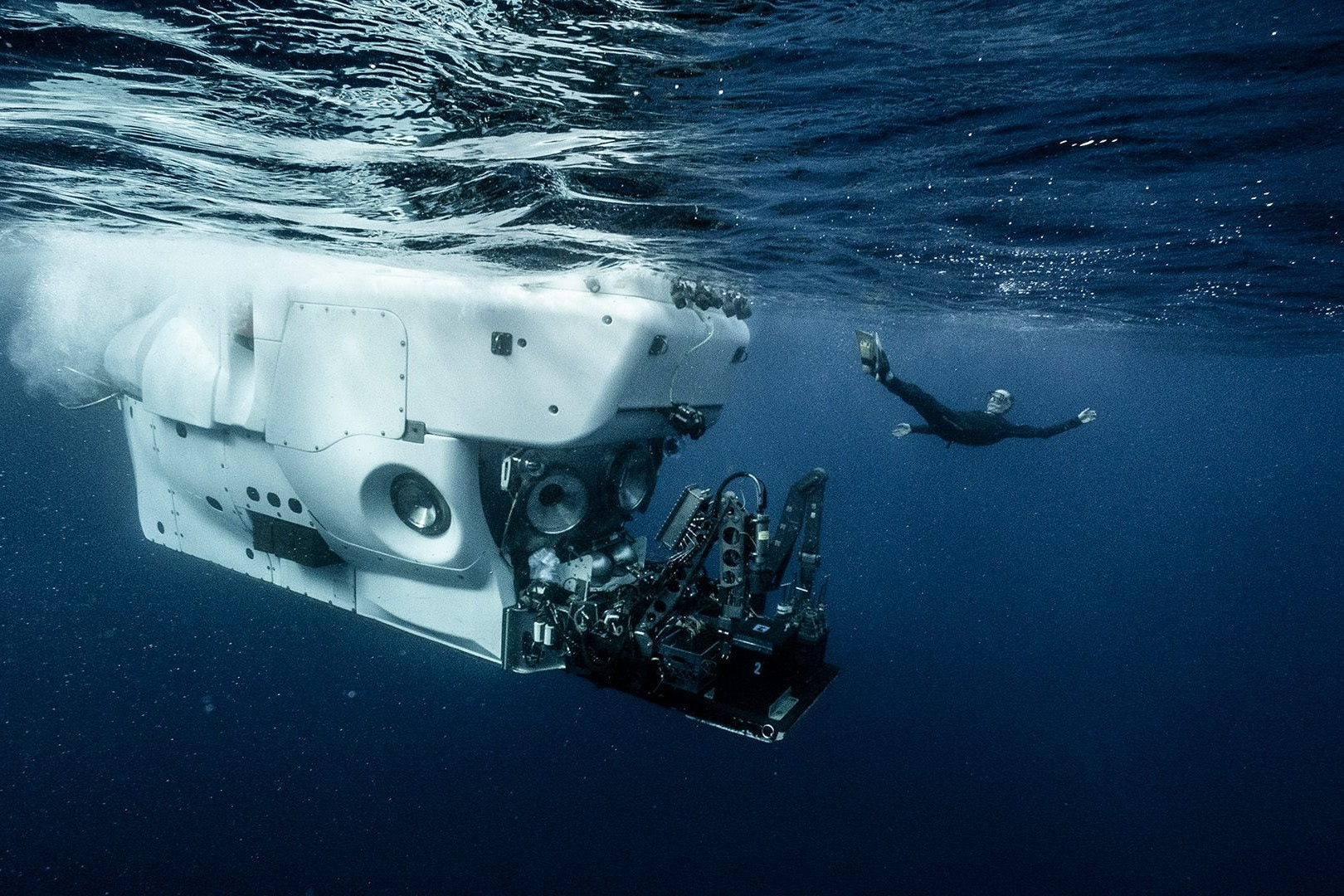

2. Submersibles and Submarines

Human-occupied vehicles (HOVs) like Alvin have revolutionized our ability to visit the deep sea in person. These small submarines are specially designed with reinforced hulls made of titanium or other high-strength materials to withstand crushing pressures at depths over 4,000 metres.

Inside, a small team of scientists and pilots can conduct research, collect samples, and observe deep-sea creatures in real time. HOVs are equipped with robotic arms for collecting rocks or organisms, ultra-bright lights, and high-definition cameras.

However, due to the limited space, oxygen supply, and intense technical demands, missions are typically short and expensive.

Fun Fact

Alvin made history in 1977 when it carried scientists to the Galápagos Rift and discovered the first hydrothermal vents—an entire ecosystem previously unknown to science!

3. ROVs: Remotely Operated Vehicles

ROVs are unmanned, tethered robots that allow scientists to explore deep parts of the ocean from the safety of a research vessel on the surface. Operated via a long cable that transmits power and data, ROVs can go much deeper than submersibles—down into trenches over 10,000 metres deep.

They are often loaded with high-definition video cameras, temperature sensors, water samplers, and robotic arms to retrieve specimens or place instruments on the seafloor. Because they don’t carry people, ROVs can spend long hours—even days—working in the deep.

Did you know?

The ROV Jason, operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, has explored hydrothermal vents, coral gardens, and shipwrecks like the Titanic.

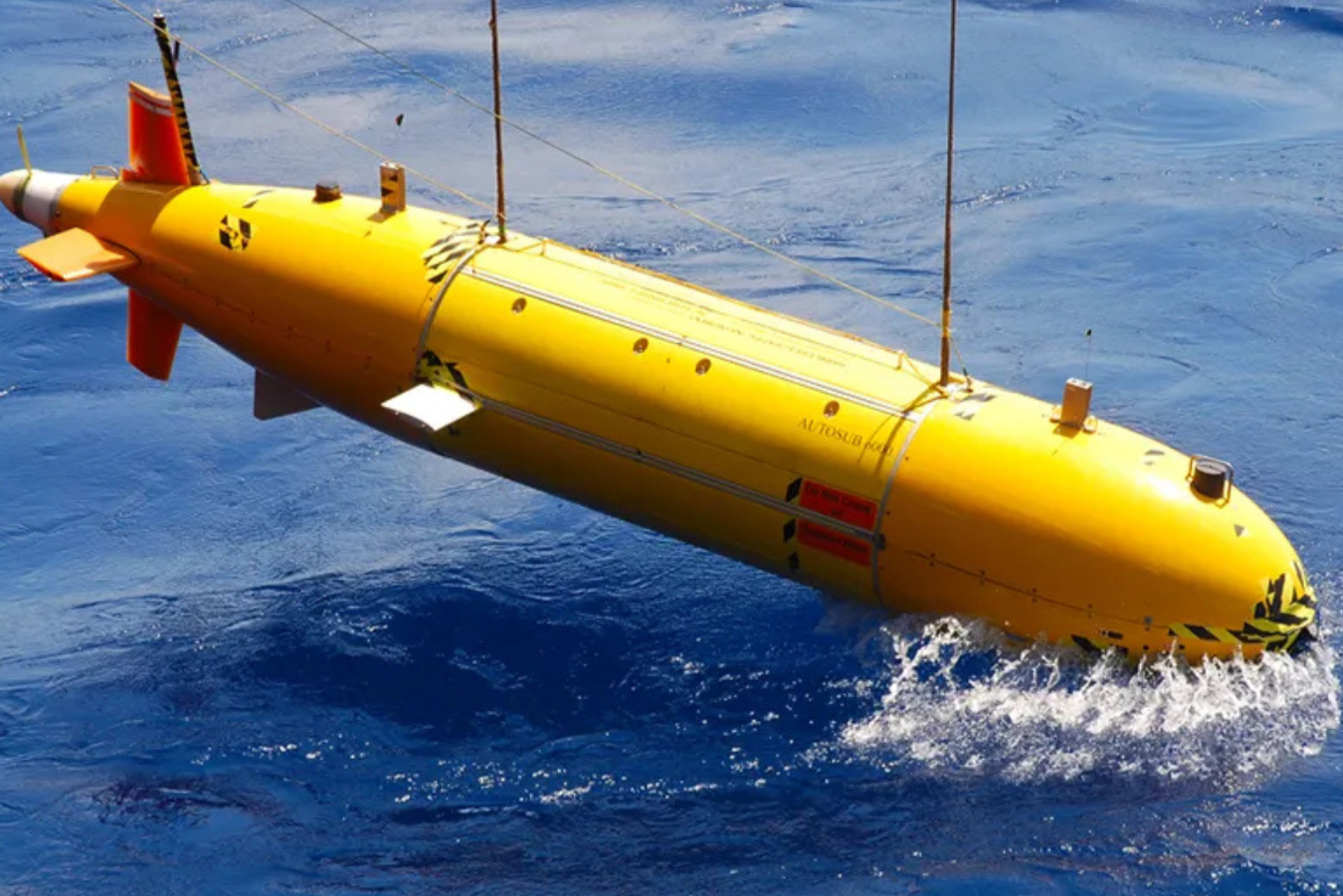

4. AUVs: Autonomous Underwater Vehicles

Unlike ROVs, AUVs are untethered and operate without real-time human control. They are programmed in advance with a mission route and can travel long distances, collecting data as they go.

AUVs use sonar and sensors to map the seafloor in high detail, detect chemical signals (such as those near vents), and monitor changes in water temperature, salinity, and pressure. They are especially useful for tasks like creating 3D maps of ocean terrain or conducting wide-area surveys where tethered ROVs would be impractical.

Fun Fact

NASA and other space agencies use AUVs to simulate missions under the icy crusts of moons like Europa and Enceladus, where alien oceans may exist beneath the surface.

5. Deep-Sea Cameras and Landers

Deep-sea landers are rugged, uncrewed platforms that are dropped from a ship and sink to the ocean floor. Once there, they sit stationary and use bait to attract curious deep-sea creatures. Cameras record footage while sensors measure environmental data over time.

Landers can stay on the seafloor for hours, days, or even weeks before being retrieved. Some are designed to automatically resurface after completing their mission, bringing valuable footage and samples back to the surface.

Because they are relatively simple and cost-effective compared to ROVs and submersibles, landers are an important tool in long-term deep-sea monitoring.

Did you know?

In 2012, deep-sea landers helped capture the first-ever video of a live giant squid in its natural habitat—an iconic moment in ocean exploration.

Conclusion

Opening the Abyss

Despite being Earth’s largest ecosystem, the deep sea remains mostly unexplored. Thanks to modern technology—submersibles, ROVs, AUVs, and landers—we’re finally able to observe, record, and study life in the planet’s most extreme environment. Each mission expands our knowledge and reveals new species, strange adaptations, and vital insights into how life can thrive in total darkness. Deep-sea exploration is not just about uncovering the unknown—it's also about better understanding our planet and, perhaps, even others.

Key Takeaways:

The deep sea presents extreme challenges—pressure, cold, and darkness.

Human-occupied submersibles offer direct observation but are costly and limited.

ROVs and AUVs allow deeper, longer, and more flexible exploration.

Landers and deep-sea cameras collect valuable data over time.

Every new tool opens a window into Earth’s final frontier.

NEXT LESSON

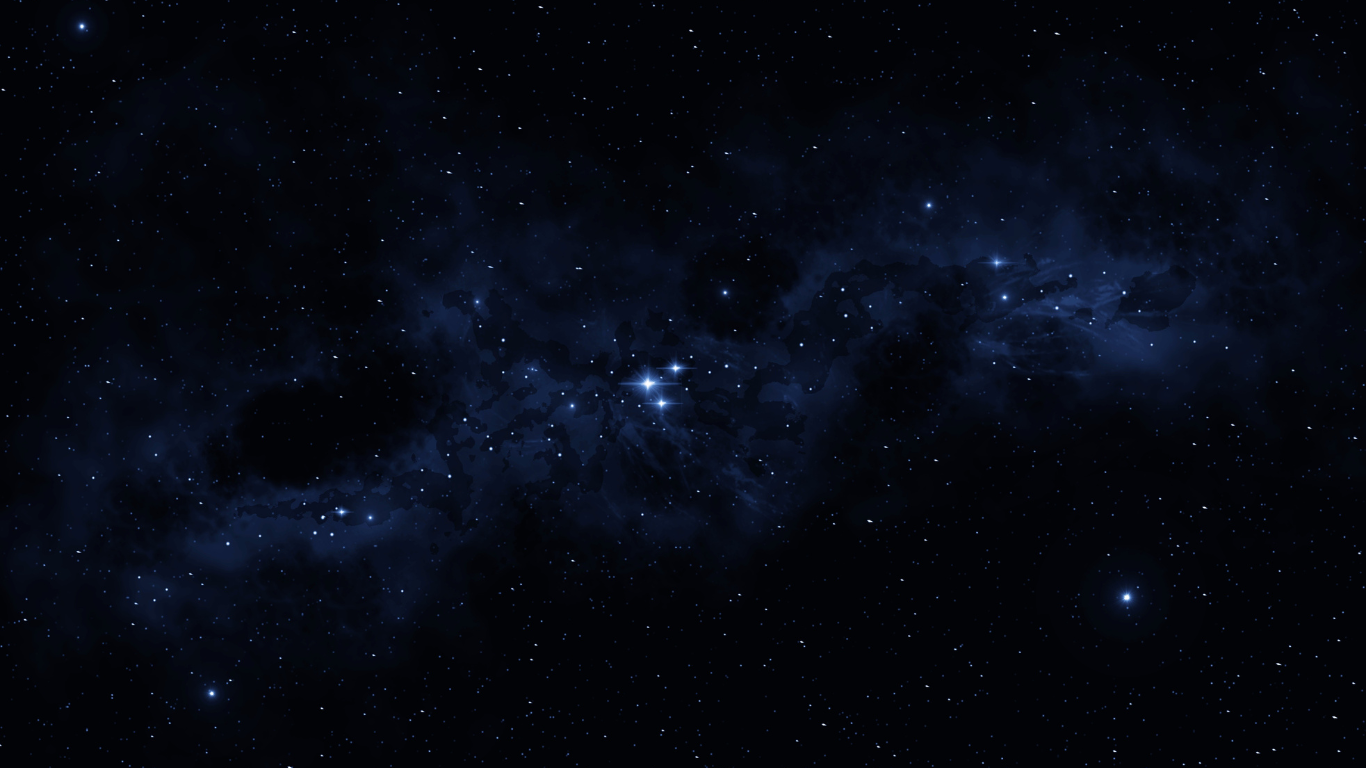

Could There Be Life on Other Planets Like in the Deep Sea?

Explore how Earth’s deep sea—dark, extreme, and alien—offers clues to life beyond our planet. Could strange creatures be hiding beneath the icy oceans of distant moons?